Let’s talk about negativity in software engineering

You are reading Compiler, a software engineering newsletter by Triplebyte editor Daniel Bean that delivers regular reportings and rantings on the industry's top news, trends and interesting players.

Happy mid-May, everyone! For this week’s newsletter, I’m taking a break from my typical hard-hitting reporting to have a discussion. The topic: negativity in software engineering.

We recently posted a blog at Triplebyte that makes a sort of symbolic argument against the “shame-inducing” name of Git’s “blame” command. If you’re not in the know, git-blame, as it’s input, is widely used during debugging to find who is responsible for a line of problematic code. Essentially, this is a feature that’s light on subtly; if it pulls your name up, you’re the coder to blame for the bug.

Writer and software engineer Joseph Pacheco explains in this blog that the command’s “fundamentally negative” name stirred him to an unnecessary degree when he met it early in his career:

The bug itself was stressful enough. Users were being impacted by something I did. But this direct (and public) association with this shame-inducing label was the icing on the cake.

Pacheco goes on to cite some research that shows how just the presence of negative words in the workplace can stifle productivity. And other research proves that if shame creeps its way in, you can say goodbye to innovation.

Read the whole article Git Should Rename the Blame Command. It's Bad for Business. over at Triplebyte.com.

Now, we all understand git-blame’s “cheeky” name was given to it by its authors all in good fun, but the joke doesn’t always translate to engineers who are fresh to the industry. And while some emotional discomfort can be a motivator for growth, even Pacheco says, needlessly negative connotation added to the otherwise productive task of having your first bugs discovered and learning from them should be done away with.

I think this argument to scrap needless negativity from software engineering, or any industry for that matter, sounds like a good one. But, as Way Spurr-Chen explained in a great (and lengthy) blog on this topic last year, it can be a fine line to walk. He thinks negativity is “embedded into our culture” and, so long as it’s properly checked, should actually play a positive role in the job of an engineer.

Discourse about programming is, above all things, extremely focused on the quality of the code written. … Negativity plays an extremely important part in programming (and human life) as a way to signal quality … It’s a signal of discernment and judiciousness or the severity of a problem.

So where does tough love or exclusionary jocularity end and stunting negativity begin in this already tough-to-crack industry? This is where you join the conversation. I want to hear your opinions, stories, or any other thoughts on the bad and good about negativity in software engineering. Leave a comment on this post or over at this blog on Triplebyte.

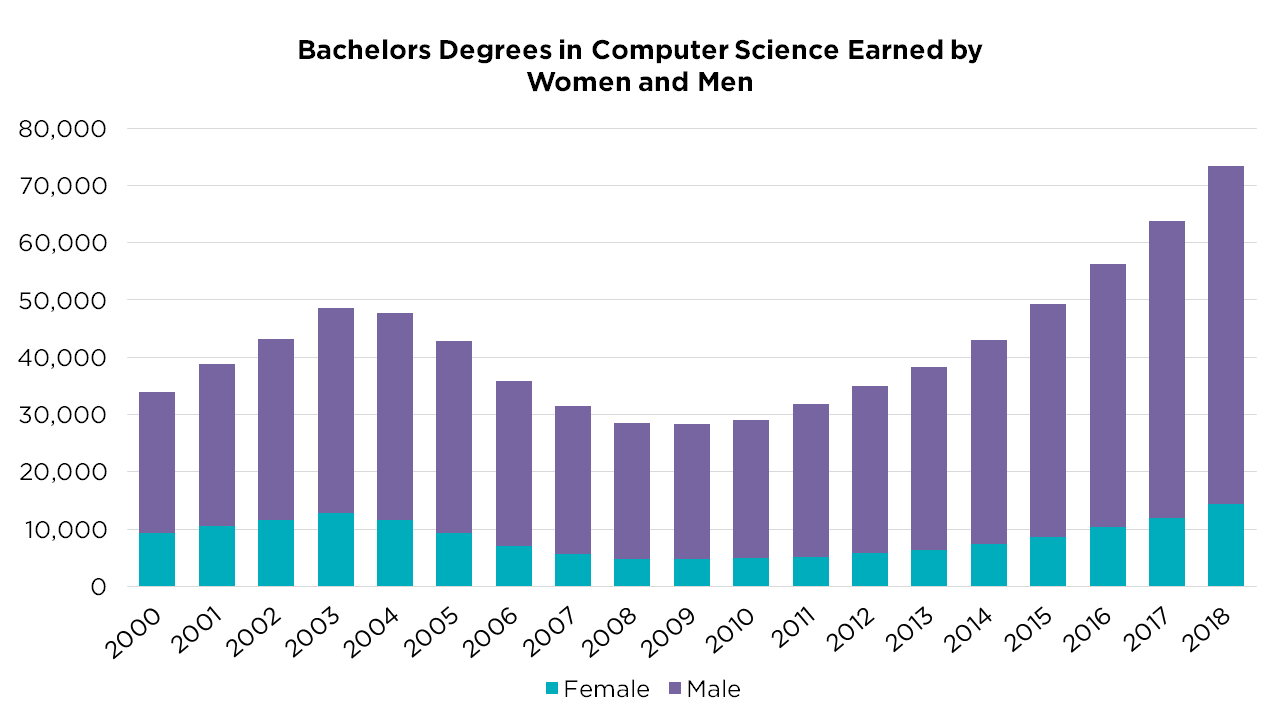

Female CS Grad Numbers Reach New Record

Seventeen years ago. That was how far back you had to go to locate the peak number of female U.S. computer science degree graduates in a single year. Until graduation data for 2018 was released this week to rip a new record, that is. With the latest numbers from Code.org showing that 14,400 women CS degree-holders marched out of college programs, the nearly two-decade dip in female participation in the educational field, which hit a low of under 5,000 in 2009, came to a close.

One point where 2003’s graduates figure still holds superiority: It represented a larger 27% of the total number of CS graduates compared to today’s 20%. That’s because male participation in CS programs have grown since 2003 to a far greater degree -- from about 36k to 59k.

Underrepresented minorities in CS degree programs, on the other hand, have seen growth in raw numbers (from about 7.5k to 13k) and percentage of all graduates (from 15% to 18%) since 2003, Code.org shows.

Quick Hits

A new recipe for single-atom transistors may enable quantum computers with unparalleled memory and processing power. SciTechDaily

AWS’s big bet on its new Graviton ARM chips could change the cloud (and the apps built for it). Protocol

The pandemic is forcing Silicon Valley to rethink the interview process. Business Insider

Python apps could soon run natively on Android devices, thanks to a new open source project called BeeWare. ZDNet

Ten successful bloggers and developers you should follow. Better Programming

From Triplebyte

I just launched a new Triplebyte blog series called “Expert.info.” (No, I don't own that website URL. Maybe I should?) Anyhow, it's a Q & A format where I ask software professionals to go deep on a technology or work practice they use and know well. First up: Superhuman CTO Conrad Irwin on how game design can make all software better.

Triplebyte has developed some new features/products to help get engineers hired during the COVID crisis. They’re all explained in detail here, including the new “Impacted by COVID” candidate tag in our platform, the soft-launch of Triplebyte Community for software engineering jobseekers to network with colleagues, and the Triplebyte “Unternship” program we’re kicking off later in May with a free webinar on how to put together a productive summer.

Some companies hiring engineers on Triplebyte right now:

Check out Triplebyte’s Actively Hiring page to find more companies that are looking for software engineering talent right now!

Tech Updates

Kite added JavaScript to its autocomplete coding tool: Available on Python for years, JavaScript programmers can now use the company’s machine learning-based “AI coding assistant” plug-in. Looks like Go is next to come!

TypeScript 3.9 was released: This is an update mostly about “performance, polish, and stability,” Microsoft says.

Triplebyte helps engineers assess and showcase their technical skills and connects them with great opportunities. You can get started here.

If you just happened upon this newsletter, subscribe with the button below to get new editions sent right to your inbox.

I think we've all been through a highly stressful early career moment when we made a mistake the cynical aspect of the culture made us think that we were being singled out or shamed. But I also think that as we grew we all learned that everybody makes mistakes and that our experiences weren't quite what we thought they were and while they were stressful they did prepare us for the nature of the job.

Software is inherently error prone and high stakes, where a single mistake could cost thousands or tens of thousands of dollars an hour and mistakes are frequent. The cynicism does guard against complacency and breeds a suspicion of faults as much as possible. Some business cultures handle this in a healthy manner and others allow that cynicism to get directed at people.

I think there is a key distinction that needs to made between negativity towards people and towards things and that we could do a better job of making that clear to new developers.

The thing is, Git is not a person. Engineers are people. The name of a silly command does not necessitate the existence of an actual blame culture in the workplace, and I think focusing on it actually detracts from serious root problems in your company if people are being finger-pointed in harmful and disrespectful ways. Our company makes extensive use of git blame to quickly pinpoint problematic code and fix it, but we also maintain a strict “no-blame” policy and work strongly as a team to come up with a solution. In a healthy company, “git blame” blames *commits*, which happen to have been authored by someone who likely has context to help fix the issue quickly; not *people*, who happened to have made a mistake.